Helping Children Understand Illness and Death

Why is it important to talk with children about difficult issues like illness and death?

“Children notice disruptions in the emotional currents of their families, so it is not unusual for them to sense that something important is happening when the adults around them are suffering grief…If they do not receive accurate information when they try to develop explanations for these disruptions, the demons of their imaginations may be far scarier than the truth about what is really happening.” (Living with Grief: Children and Adolescents, edited by Kenneth J. Doka and Amy S. Tucci, Hospice Foundation of America, Washington, D.C., 2008, page 7)

“We want to protect our children, so we avoid telling them hard truths. But when we pretend everything is okay when it isn’t, we risk losing their trust. It’s important to tell the truth with love and hope. We also need to be honest about our own feelings. It’s healthy for children to hear adults say that they’re sad, too.” (Debi Lillegard, MA, LMFT; Park Nicollet Clinic, St. Louis Park, Minn.)

How do you talk to a child about the illness of a close family member?

“When talking with children about difficult topics, keep explanations simple and brief: ‘Mom is really sick and needs to go to the hospital where doctors can help her get better.’ Also, focus on how the illness directly affects the child. ‘While Mom is at the hospital, Mary will pick you up from preschool and take care of you.’

“Give a little information and let the child ask questions. Children will ask different questions, depending on how they look at the world. One child will ask whether Mom will still tuck him into bed. A concrete answer provides security: ‘While Mom is in the hospital, I will tuck you in or Mary will tuck you in.’ Another child will ask about the illness. In the case of cancer, you could say, ‘Mom has some bad cells in her body that are eating the good cells, and this is making her tired. She is going to the hospital, where the doctor can try to get rid of the bad cells.’ The child might even ask you to draw a picture of the cells.

“Try to answer children’s questions when they ask them—in two sentences or less, if possible. If you give children too much information at one time, they won’t absorb it.” (Signe Nestingen, Psy.D., LP, M.A., LMFT; greatrivertherapy.com)

How do you prepare a child to visit a loved one in the hospital?

“It’s important to talk about the people, sights, noises and smells a child will experience at the hospital. If the family member’s appearance has changed, you should talk about that ahead of time. Also, you might encourage the child to bring a favorite stuffed animal or toy for comfort and security.

“Once you get to the hospital, make stops along the way to the room. Stop in the hospital entryway, the nurses’ station, the family waiting room, etc. At each place, ask the child what she notices. This may help prepare her for the hospital room.

“Parents also can help children find new ways to engage with the person who is ill. Could the child read or tell stories to Grandma? Could she bring snacks or an activity to Grandma at home or in the hospital instead of going out? The family needs to modify activities based on the ill individual’s capabilities at that time. Ideally, the family approaches these limits as an opportunity to cultivate new ways to connect.” (Diann Ackard, PhD, LP; Golden Valley, Minn.)

“Be honest and concrete: ‘Sometimes people who are sick look different—maybe even a little scary. Grandpa’s skin is pale, and he is connected to a machine that helps him breathe. He might not be able to talk.’ Tell the child that it’s okay if he doesn’t want to touch Grandpa or sit on his bed—and it’s okay if he wants to leave the room.

“Some children are apprehensive about hospital visits, but others are more curious than scared. I’ve worked with children who were angry that parents didn’t include them in hospital visits.” (Daena Esterbrooks, counselor, Growing through Grief)

How do you prepare a child for the impending death of a family member?

“Tell children the symptoms of the illness are getting worse and the patient is getting weaker. You might say, ‘The cancer is in so many parts of Grandma’s body, it is hard for her body parts to work and she won’t be able to live much longer.’ Let children know how the illness might progress and what they might expect. Answer their questions openly and honestly and help them find healthy ways to say goodbye.” (Lillegard)

“It’s important to be honest and use concrete language: ‘I need to talk with you about something that might make you feel sad. Grandma is really sick. It’s not like when you had a cold last week and got better. Grandma’s sickness probably won’t go away. Soon she will become so sick she won’t be able to live anymore.’

“When you talk to a child, use concrete words, like dying, rather than euphemisms like ‘passing away,’ ‘going to sleep,’ or ‘going to a better place.’ If you talk about the person going to Heaven, make sure the child understands that Heaven is not a place you can visit—that only people who have died can go there. And make sure children understand that once a person has died he cannot come back. I once counseled a 5-year-old who told me that over spring break the family was going to visit his dad in Heaven. Parents have the best intentions but sometimes forget that children are very concrete—and if they don’t understand they fill in the gaps.” (Esterbrooks)

“When speaking about death and grieving to your children, truth and honesty are always the best approaches. Being truthful and honest is not the same as being blunt and insensitive. You can talk about death and grieving in a warm, caring, sensitive way.” (Helping Children Cope with the Loss of a Loved One: A Guide for Grownups by William C. Krooen, Ph.D., LMHC, Free Spirit Publishing: Minneapolis, 1996, page 10.)

“Remember that children live in the present; they can’t process the idea of someone having five months to live. If possible, try to address practical issues before talking to young children. Knowing that there is a plan can help make them feel more secure. If hospice workers are coming into the home, or the family routine is changing, it’s important to explain the change to the child. Tell her, for example, that nurses are coming on Tuesday, and that you will move Dad’s bed into the living room. Then remind the child the night before.

“At some point, you need to tell the child the person is dying. The child might ask odd questions: ‘Who will walk the dog?’ or ‘Will Mom still be here for breakfast after she dies?’ You need to answer hard questions honestly: ‘No, Mom won’t be here.’ As parents, we don’t want to say such hard things to a child. But we need to explain death in an honest and concrete way or we risk confusing the child and losing her trust. At the same time, the child needs the security of knowing someone will always take care of her.

“In talking to children, be careful about the use of euphemisms. Avoid saying things like, ‘Remember when we put the dog to sleep? Now Grandma is going to sleep.’ How does the child know that he won’t go to sleep in the same way?” (Nestingen)

“Understand that children are not likely to grasp each of the central dimensions of the concept of death or all its implications at once. That is one reason they repeat their questions about death or ask them again in different ways…

“Realize that one good way—perhaps the only effective way—to gain insight into a child’s understanding of death is to establish a relationship of trust and confidence with the child and to listen carefully to the child’s comments, questions and concerns about death…

“Frame your answers and responses in ways that are suitable to the child’s capacities and needs. Don’t be afraid to say, ‘I don’t know.’” (Living with Grief, page 41)

What are the typical fears or responses of a child dealing with the illness or death of a loved one?

“A child usually won’t say, ‘I’m sad that my Grandma is dying.’ He doesn’t have the words or cognitive ability to express his feelings directly. Instead, he might say, ‘I don’t like recess; it’s not fun anymore.’ As a counselor, I try to help the child talk about what he might be feeling. I might say, ‘When we’re sad, we sometimes don’t feel like doing the things we usually like.’ If the child says her tummy hurts, I might say, ‘Sometimes you feel sadness in your tummy.’ I try to help children understand how their feelings affect their bodies— to show them they’re not sick but sad. Children’s thinking is pretty black and white, and they often need help to make these connections.” (Esterbrooks)

“Typically, young children express three fears: Did I make this happen? Can I catch it? Who will take care of me?

“A child hearing that Grandma has stomach cancer might remember that last week, when he and Grandma were playing ball, the ball hit her in the stomach. He might actually believe this caused the cancer. Children come up with all sorts of ways they could have caused the illness or death. Parents can help by saying, ‘Sometimes when someone dies, people around them think they did something to cause it. But nothing you—or anyone else—said or did could make this happen.’ It’s important for an adult to bring up this topic, because the child probably is afraid to ask the question out loud.

“Second, parents should explain that the death or illness is not contagious. Even for teenagers—especially those who have suffered several losses—death can feel contagious. Adults can help by reminding the child or teenager that most people don’t die until they reach old age.

“Third, if a parent has died, I recommend that the surviving parent sit down with the child and make a list of ten other people who could take care of her. Certainly, children don’t want their parents to die, but it’s comforting to know there is a plan. At the same time, the surviving parent could reassure the child: ‘Dad did die, but most people don’t die at age 40. You’ll probably be a grown-up with children of your own before I die.’” (Esterbrooks)

“A surprising number of the children were afraid that they were going to forget their dead parent. This fear can be addressed in several ways. One of the easiest ways is to help the children create a memory book…Another way to remember the dead parent is to include the parent in daily conversations in a natural way.” (Living with Grief, page 130)

Should children attend funeral services of parents or other close family members?

“In general, children should be given the choice of participating or not, although adults should make the decision for preschool children. However, when giving children a choice, it should be an informed choice. Better outcomes were observed in the children who were prepared for the service…

“If younger children are participating, designate an adult (not an immediate family member) who can sit with the child and take him or her outside or to the bathroom if needed.” (Living with Grief, pages 132-133)

“As a general guideline, children six years old and up should be allowed to attend if they want to. Joining family members and friends for these important rituals gives children a chance to express their grief, gain strength and support from others and say good-bye to the loved one…

“Be sure to prepare them ahead of time by explaining what will happen and what they will see, hear, and do. Tell them whether the casket will be open or closed. Explain that many people will probably be crying. Let them ask questions.” (Helping Children Cope with the Loss of a Loved One, page 5.)

How can parents help their children when they themselves are struggling with stress or grief?

“It’s a real challenge for a parent to balance his or her needs with the needs of the individual who is ill and the need to be with the child. It’s a matter of determining what is the priority in the moment. Sometimes this means shifting the times of various events, but it’s important not to lose them entirely. For example, a tradition such as a weekly lunch date, can become even more meaningful and significant when you have to make the effort to find a new time. Yet it is still crucial to preserve its occurrence.” (Ackard)

“Families experiencing loss need strong support systems. The parent needs her people; the child needs his people. Allowing others to provide both emotional and practical support (delivering meals, providing rides, etc.) makes a real difference. If you are a single parent, do whatever it takes to make sure you have help. Then you will have more left to give your child.” (Nestingen)

“Being a parent is tough, and the difficulty increases tenfold when you are going through grief. Parents need to take care of their own needs—and they need a time and place where they can fall apart for a while. At the same time, it’s important to let your children see you cry or even express anger. Children learn through modeling; if they don’t see you expressing emotion, they’ll think it’s not okay to feel sad or angry.” (Esterbrooks)

“Grieving children sometimes believe it is their job to care for and protect their surviving parent and make the parent feel less sad. Counselors can communicate to children and to their surviving parents that although the children can let their parents know that they are there for them and hope they feel better soon, children are not responsible for making their parents feel less distressed or for addressing issues such as having less money…Counselors can work with parents to ensure that they are not entangling children in the problems of the family, encouraging parents to find ‘adult ears’ to listen to their problems.” (Living with Grief, page 147)

How can you help a child survive a devastating loss—such as the death of a parent?

“Ultimately, you need to give the child time to grieve. It’s also important to provide outlets for the child to express her feelings—such as crying with her surviving parent or another adult, punching a pillow, coloring or playing video games. I also urge the surviving parent to find another trusted adult the child can talk to. It could be someone at school or church, a family friend, or another relative. Sometimes the child won’t talk to the surviving parent because he is afraid of making the parent sad. The child loves you so much he wants to protect you.” (Esterbrooks)

“The best thing a parent can do is love the child through her grief and make sure she has attachments to other adults. As a family, you just need to live through the hard period. Our natural response is to want to make the grief go away, but it doesn’t. Sometimes all a parent can do is sit down with the child or children and figure out how they will get through the hard times together—and reassure the children that ‘we are still a family.’” (Nestingen)

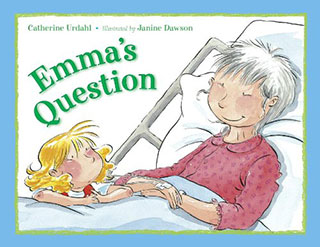

written by Catherine Urdahl

illustrated by Janine Dawson

Charlesbridge, 2006

Find this book at your public library

or your favorite used bookseller.